Why do we paddle? For some it is the peace of a quiet day on the water. For others it is the thrill of running a wild river, or riding a crashing wave. Whatever your motivation, there is no doubt that paddling involves risk, and understanding these risks can help us become better paddlers.

Putting Risk in Perspective

In life, risk is unavoidable. Looking at the risks that we face over our lifetime we find that chronic disease is by far the most common cause of premature death. Fortunately, most of us can expect to live long and active lives, and the most important thing that we can do to manage this risk is eat right, exercise and maintain a healthy life style - in other words, get out there and paddle!

In terms of accidental death, riding in a car is statistically the riskiest thing that we do every day. We are much more likely to be involved in a car accident riding to/from the put-in than we are to be involved a boating accident. Boating accidents are rare, and paddle sport accidents involving experienced paddlers are almost nonexistent – almost!

While paddle sport accidents are rare they do occur. The American Whitewater Accident Database catalogs over 1,600 fatalities and close calls on whitewater rivers dating back to 1972. Lest the sea kayaker community feel left out, there is also the case of Douglas Tompkins, a noted conservationist and the founder of the North Face and Esprit clothing brands, who died in a kayaking accident in the Patagonia region of southern Chile in 2015.

Risks, Hazards and Risk Reduction Strategies

We need to understand a couple of definitions as we begin to look at risk management for paddlers – Risks, Hazards and Risk Reduction Strategies.

“Risks” are things that can go wrong when we paddle. They can be things that happen to the paddler (drowning, hyperthermia, blunt trauma, lacerations, exhaustion, dehydration), to the paddler's equipment, or can be situational like getting lost.

“Hazards” are conditions that increase a risk. Hazards can be related to human factors (skills, equipment or physical condition), environmental factors (weather, tides, water levels or physical obstructions like rock, ledges, strainers, or shoreline access); or can be situational (planning, navigation or leadership).

For example, cold water paddling is a hazard that increases the risk of hypothermia. Risks and hazards don't operation in isolation. They often build upon themselves making the situation more dangerous.

“Risk reduction strategies” are ways to reduce a risk, or eliminate it entirely. Risky situations have a way of progressing from routine events to serious accidents.

Risk mitigation strategies attempt to break the chain that leads to serious accidents - like wearing a drysuit or wetsuit in cold-water conditions. Other risk mitigation strategies include wearing a PDF (always), having appropriate skills and equipment for the trip, and paddling in group with appropriate skill levels. The ultimate risk mitigation strategy is avoidance - like knowing when to change or cancel a trip. While avoidance is an important strategy for dealing with the most dangerous risks, it is not a strategy that can be applied in all situations, or we would never paddle at all.

Real vs. Absolute Risk

A risk at its most dangerous level is called the “absolute risk”. Through risk reduction strategies we can reduce the level of risk to a more manageable level, which is called the “real risk”. In most cases, a paddler’s objective is not to eliminate risk entirely, but to use risk reduction strategies to match the real risk to that paddler’s experience and skill level.

Real vs. Perceived Risk

Difficulties can arise when a paddler’s subjective assessment of risk does not match the real risk. This is especially true if the paddler’s “perceived risk” is significantly less than the real risk, putting the paddler in danger of physical harm. This is a frequent cause of accidents with inexperienced paddlers. At the other end of the spectrum, if a paddler’s perceived risk is significantly higher the real risk, that paddler may be avoiding situations that are within their skill level, and that they would find fun and rewarding to paddle.

Accurately matching the real and perceived risk is a skill that comes with experience. There are number of factors that might affect our perception of risk at any given time including our confidence level, enthusiasm (get-moreitis), experience with the trip or similar trips (familiarization), training, physical condition (tired, hungry, etc.) and group dynamics (peer pressure and risk shifting). It is important to understand how these biases effect our evaluation of risk.

How Much Risk Is Acceptable

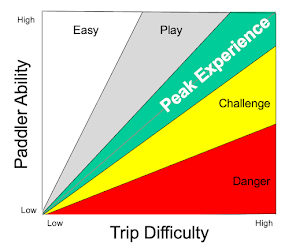

Determining the amount of risk that we wish to take is a very personal decision. Some paddlers prefer easy trips that barely challenge their capabilities. Other paddlers prefer to push the extreme, always paddling at the edge of their ability. For most of us, our “peak experience” lies somewhere in between – just enough to provide a challenge, but not enough to put us in danger.

Personally, I enjoy a mix of trips – some easy, some more challenging. I also think it is important to occasionally push the envelope with more challenging trips as a way to improve my paddling skills. While this opens the door to new and interesting trips with new and interesting people, I also recognize that it must be done with an eye toward safety. Even trips that we know well can change, and conditions must be constantly assessed and managed.

Managing Risk

The ongoing process of assessing and managing risk is called the “risk management process”. This process is often taught in outdoor leadership programs as a way to manage group risk, but is also useful for individual paddlers as they decide whether to participate in a particular trip. The process includes identifying the trip, evaluating the risks and hazards, assessing risk mitigation strategies, and then (and only then) determining whether to participate in the trip.

The process starts with an identification of the trip - what are the conditions I will face, who is in the group I will paddle with, and how do these factors match with my experience, skills and equipment. If the risks are acceptable I will participate in the trip. If not, are there additional risk mitigation steps that I can take to reduce my risk to an acceptable level - will the leader show me the easy lines, or can I walk the more difficult rapids. Only when these modifications are in place should I agree to participate in the trip.

While this assessment should always take place at the start of a trip, it shouldn’t stop there. Everyone needs to be aware of changing conditions and make adjustments accordingly.

What about Trip Leaders?

Of course, most of us don't paddle alone. While the notion of a "trip leader" is antithetical to some paddlers, having someone planning and thinking about risk management issues in advance is important for the group.

How leadership responsibility gets distributed in the group depends a lot on the group. Leadership can be hierarchical with responsibility residing in a single individual, shared with everyone sharing responsibility, or something in-between.

The most oblivious example of a hierarchical structure is the military with its formal chin of command. This is a structure that everyone understands, and typically happens on guided trips.

At the other end of the spectrum is the shared structure where everyone is involved in leadership. When friends get together for trips this is often the structure they adapt. It works best with folks who know each other well and are willing to move from leader to follower depending on the situation and the skills needed.

Many trips fall somewhere in-between in a delegated/designated structure with an a formal or informal "trip leader" working with other members of the group to make sure that critical tasks are covered. Most club trips are structured this way.

Its all about Personal Responsibility!

Like everything in life, paddling is a sport that involves risk. While these risks can be managed, short of staying home they cannot be completely avoided, and each paddler must be responsible for their own safety. Paddle safe, paddle smart, and always wear your PFD!

Based on Managing Risks in Outdoor Activities (Outdoor Safety, Mountain Safety Manual 27) – 1993 by Cathye Haddock (Author), New Zealand Mountain Safety Council (Author), Pippa Wisheart (Editor)